Well, the pressure is on – after getting Freshly Pressed last week, I realised I could no longer blog about how boring it was to be unemployed, and how I filled up my time playing computer games (or well, I could, but it would be a bit of a come-down).

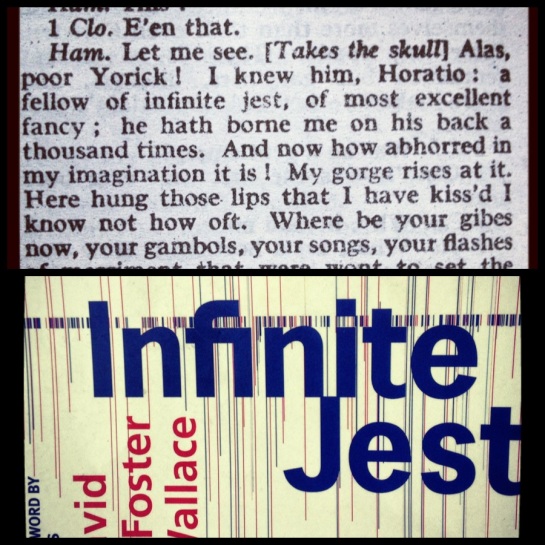

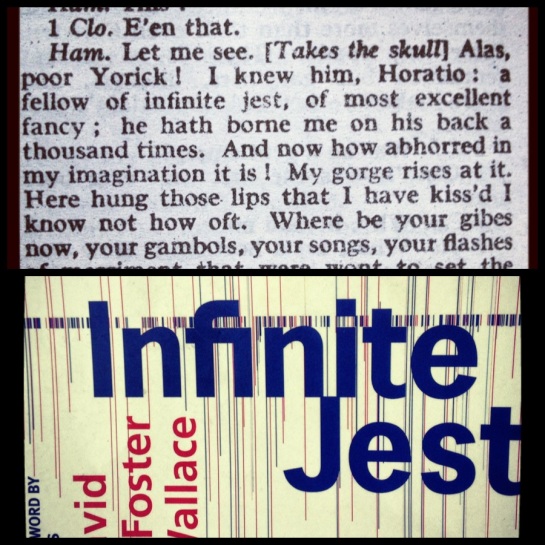

Clever allusive titles – gotta love ’em.

But luckily, I had a few weeks ago embarked on what can only be described as a literary journey, and a long one at that: I began reading David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, hailed (in that adulatory section before the story begins) as “[showing] signs, in fact, of being a genuine work of genius” (Esquire, US) and as “fascinating, ridiculous and excruciating, and a stimulating injection into contemporary American culture” (Independent on Sunday). This is all high praise indeed, and since I’m not the greatest with contemporary fiction (I only read Philip Roth for the first time a few months ago…), I thought I’d do well to read this mammoth work and see for myself. Well, so far it is all that and more – it is brilliant; it’s amazing and it’s difficult, but it’s also worth it.

What first drew my attention to David Foster Wallace was an article about his life and suicide; it was something I stumbled across, somehow, when I was idly reading articles on the net a year or so ago to kill some time between something and something else. Thus begins the article (an old one, and oddly enough, in the New Yorker now that I’ve looked it up – I hadn’t been reading this publication then!):

The writer David Foster Wallace committed suicide on September 12th of last year. His wife, Karen Green, came home to find that he had hanged himself on the patio of their house, in Claremont, California. For many months, Wallace had been in a deep depression.

I know it’s cheesy, if not downright weird and uncomfortable, to be intrigued by an author because they were depressed and then committed suicide. For this fact says nothing about the merit of their work, fundamentally. But I was curious for this very reason. David Foster Wallace’s story was tragic and somewhat Keatsian – he was 46, and many people say that he died before he had done his work the way he wanted to, or written as much as he should (could? is should too imperative?) have. Also, the tortured artist is not a prevalent figure in society these days. The Virginia Woolfs, Charles Bukowskis, and Vincent Van Goghs of yore have left us with an enduring idea: that of the genius-artist who is so brilliant that they are driven mad, made depressed, rendered alcoholics, driven to suicide, etc. The list is endless. Until David Foster Wallace, I couldn’t really think of many contemporary/recent artists who actually adhere to this characterization, however. (There is one other – the playwright Sarah Kane, who wrote an insane play called Psychosis 4.48, and then committed suicide.) Before continuing on with D. F. Wallace, I have to digress on how unusual and uncommon the figure of the ‘tortured artist’ has become in our day and age.

I was translating a poem by Rimbaud the other day (in an attempt to keep up with/improve my French – I find translating is a good, engaging way to learn a language, and infinitely more interesting than memorizing endless reams of grammar notes alone), and got stuck at how to render the words, “la magique étude du bonheur” (the magical study of happiness). In trying to read around what it might mean, I came across a book by Giorgio Agamben (one of my favourite contemporary theorists, who I used extensively in my Master’s dissertation and who has many, many interesting things to say about the post-9/11 experience etc., for those who are interested in all that), called The Man Without Content. He begins by describing the Kantian characterization of aesthetic experience, which stresses impersonality and disinterestedness (i.e., there is no personal investment in the aesthetic object). He then describes (and agrees with) Nietzsche’s critique of this view, which states that ‘disinterest’ is only the fortunate possession of the spectator, and not the artist/creator, who must always necessarily invest – be interested – in what he creates; Nietzsche writes (as quoted by Agamben),

This is not the place to question whether this [Kant’s view] was essentially a mistake; all I wish to underline is that Kant, like all philosophers, instead of envisaging the aesthetic problem from the point of view of the artist (the creator), considered art and the beautiful purely from that of the ‘spectator’, and unconsciously introduced the ‘spectator’ into the concept ‘beautiful’.

….

“That is beautiful,” said Kant, “which gives us pleasure without interest.” Without interest! Compare with this definition one framed by a genuine ‘spectator’ and artist — Stendhal, who once called the beautiful une promesse du bonheur [a promise of happiness]. At any rate, he rejected and repudiated the one point about the aesthetic condition which Kant had stressed: le désinteressement. Who is right, Kant or Stendhal?

(As a side note – the link with Rimbaud becomes obvious after reading Stendhal’s statement, because both artists see art as related to the ‘promise of happiness’, somehow – perhaps art is the space of Rimbaud’s search for happiness, the thing which promises it him.) The rest of Agamben’s chapter devotes time to exploring this divide, between the artist’s experience of art (heavily invested, interested), and the spectator’s experience of art (disinterested, in the Kantian sense). He quotes Baudelaire, who says the artist’s act of creation is “où l’artiste crie de frayeur avant d’être vaincu” (“where the artist cries out in fright before being defeated”); he quotes ‘the note found in Van Gogh’s pocket on the day of his death’, which reads, “Well, as for my own work, I risk my life in it and my sanity has already half melted away in it.” (I do not think D. F. Wallace would disagree with this sentiment!); and he refers to Rilke, who writes that “works of art are always the product of a risk one has run, of an experience taken to its extreme limit, to the point where man can no longer go on”.

But who says such things about, or even invests such emotions in, art these days? These words make a strange contrast to the capitalist rhetoric of ‘use’ that is currently seeing humanities funding being cut everywhere, arts industries suffering financially, art being classified as a ‘luxury’ that we ‘can’t afford’ in times of economic trouble. There are undoubtedly people who do see their art as such a madness, as such a ‘risk’ – what else can possibly be said about Rushdie’s stance in the face of a (recently-reiterated) bounty on his head (indeed, the price has gone up by US$500,000!)? Or Coetzee writing first in the midst, and later in the aftermath, of apartheid and extreme censorship, and despite it? Of course the writers (and other artists) of our age invest something in their art, if not (à la Van Gogh) half their sanity, something beyond the norm, and I am not trying to say they don’t. But David Foster Wallace towers above everybody I can think of and love (Rushdie, Roth, Coetzee, Kundera etc.) as the ‘tortured artist’ of our times; articles about his death and writing always stress how difficult writing became for him before he committed suicide, and perhaps his investment in his work was less socio-political than it was personal, more an investment of the psyche and soul.

Having rambled (ho ho!) at length about the man, I guess I must needs now talk about the book. I am nowhere near finishing: it’s a whopping 1079 pages, in small print, and it’s not written in a form that allows for streamlined, straightforwardly linear reading. One of Wallace’s most distinctive traits, which I love, is his use of endnotes (I really love using footnotes in my own stories, and while I do like footnotes better than endnotes, because they’re right there at the bottom of the page and don’t necessitate turning right to the end of a very-long-book, the same principle applies!); in a much more eloquent way than I ever could, he describes his need for endnotes thus (from the above-linked New Yorker article):

He explained that endnotes “allow . . . me to make the primary-text an easier read while at once 1) allowing a discursive, authorial intrusive style w/o Finneganizing the story, 2) mimic the information-flood and data-triage I expect’d be an even bigger part of US life 15 years hence. 3) have a lot more technical/medical verisimilitude 4) allow/make the reader go literally physically ‘back and forth’ in a way that perhaps cutely mimics some of the story’s thematic concerns . . . 5) feel emotionally like I’m satisfying your request for compression of text without sacrificing enormous amounts of stuff.”

What I really like about them stylistically is that they allow the author to do what Virginia Woolf writes about in one of her many diaries (August, 1923, though she isn’t writing about footnotes): “dig out beautiful caves behind my characters: I think that gives exactly what I want; humanity, humour, depth. The idea is that the caves shall connect and each come to daylight at the present moment” – in Wallace’s work, they come out in the endnotes. The endnotes make me a much slower reader of this already-difficult book than I otherwise would be, but — that’s all part of the plan, I guess!

Infinite Jest is, as New Woman aptly identifies in an adulatory quote, “an insight into modern addictions and spiritual frustrations”: it’s about drugs drugs drugs – the psyche which needs drugs, the psyche after drugs, the psyche without drugs, you name it. It’s a darkly satirical world sometimes, and in this I can see something distinctly American (I’m not sure what, but it is American). The sort of dark hilarity that comes out in Wallace’s work sometimes (e.g., when he’s describing the effect of a certain drug as “pulmonary sloth” – people becoming too lazy to even breathe, and dying as a result) is highly reminiscent of the sort of thing I associate with John Irving’s The World According to Garp and even Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, books that make you laugh and cry in fits and turns and sometimes simultaneously.

And perhaps this prevalence of drug addiction is, as New Woman seems to suggest, very much linked to the spiritual frustrations of a highly-capitalist world (Infinite Jest’s dystopic setting is a future where even the years are named after corporate things; corporations ‘subsidize’ time by buying rights to name the year or something, hence ‘Year of the Trial-Size Dove Bar’ — damn you, Dove!). Sometimes strangely enough, disparate things you’re reading unintentionally coalesce, and while I was reading (wait for it!….) the New Yorker (da dum!) last week, I came across a ‘personal history’ piece by Oliver Sacks (again! you come across someone once and take note, and then suddenly they’re everywhere!), on his drug-addled youth. The start of his article (called ‘Altered States’), explores answers to the question, why drugs? Why – because

To live on a day-to-day basis is insufficient for human beings; we need to transcend, transport, escape; we need meaning, understanding, and explanation; we need to see over-all patterns in our lives. We need hope, the sense of a future. And we need freedom (or, at least, the illusion of freedom) to get beyond ourselves….

And drugs, he says, “offer a shortcut; they promise transcendence on demand.” It’s a powerful answer and statement, one which I felt was intimately connected to Wallace’s world in IJ. In a world where God and religion are no longer means for such a transcendence, or out-of-self elevation/transportation, drugs are a quick and easy alternative; capitalist secularism’s version of transcendence and ecstasy (ho ho! pun intended), if you will. Some of the characters in the book have an almost ascetic, ritualistic relationship with drugs – they cut themselves off from ‘real life’ almost entirely, refuse to answer the telephone or go to work, lie in bed at home all day staring at the ceiling, etc etc. These things necessitate an elaborate ritual before and after, and weed-scented rooms become the refuge of these postmodern, somewhat fucked-up ascetics. Wikipedia on ‘asceticism’ and its earliest practitioners: “They practiced asceticism not as a rejection of the enjoyment of life, or because the practices themselves are virtuous, but as an aid in the pursuit of salvation or liberation.” I think in Wallace’s world, ‘liberation’ (but from what? from life itself?) is key.

I haven’t read enough of the book to pursue this idea further, but it was an interesting connection between the timely Sacks article and the novel that occurred to me, and I thought it was worth noting down (nor is this relationship – between addiction and spiritual frustration – necessarily limited, after all, to Infinite Jest – it’s very much prevalent in our lives, in our world right now, and it bears thinking upon). After IJ, which may be a while, I hope to read a book recently nominated for the Man Booker prize 2012, Narcopolis by an Indian writer called Jeet Thayil; also about addiction and its place in the modern world. There might be interesting thematic parallels.