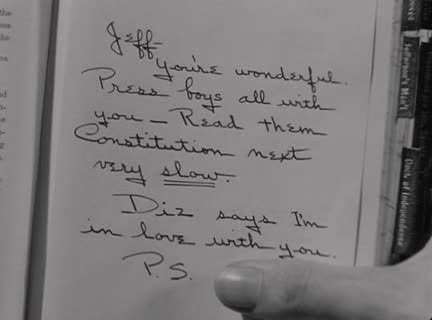

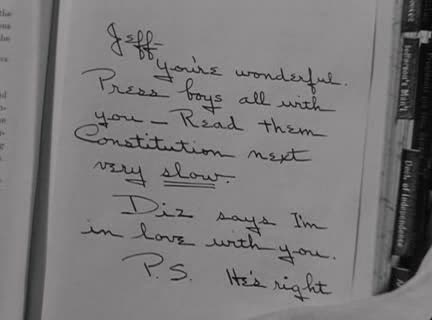

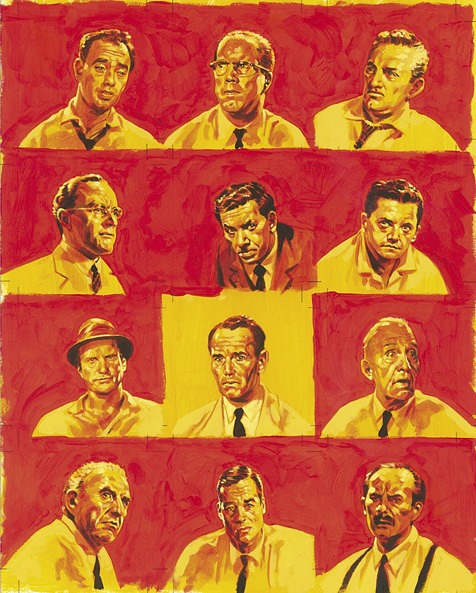

The aforementioned ‘Men’.

In a post-religious world, where all-guiding tenets have lost their charm (& widespread power, too), the words “crime & punishment” are almost inseparable from each other: they almost always work in semantic and syntactic tandem. Where there is crime, the law & justice conspire together to say, there must rightfully also be punishment. And where there is punishment, there must surely have been a crime. This much was axiomatic even long before Dostoevsky articulated and elucidated it with his famous novel. Sinners are nowadays ‘criminals’, and they can no longer look to the skies for redemption or forgiveness (God seems almost gentle in the facility with which he can bestow them). Rather, state and society have taken upon themselves the burden of dispensing both – in the form of jailterms & prison-cells, electric-chairs & straitjackets.

Do your time, we are told (for ‘time’, somehow, becomes the currency in which we buy these things), and maybe 20, 40, 70 years hence you can go back to the world and begin anew. Anew, and better. That’s the hope, anyways. (Sometimes, ‘time’ is no good, hardly a fair exchange given the scale of the crime – for how can time, even all of it in the world, bring the dead back to life? And what solace can one man’s time provide to those left behind grieving? In such cases, only life will do. Maybe misery and penury and suffering in life impelled you to the crime, but now you’ve forfeited your right even to that miserable thing. And so quickly, painlessly, it’s extinguished – minimal fuss, and in the long run, perhaps cheaper for the state, too.)

Crime, & punishment. Somewhere in between those two vicious extremities (for though punishment may be just, it has to hurt at least a little, else it’s powerless to affect) come the chase, à la film noir & detective novels. Then the confession, drawn out sometimes in excruciating degrees (though for a reader or a cinema audience, so very delightfully suspenseful and thrilling). Sometimes there’s even repentance – for even suspense thrillers have a vague memory, sometimes, of how confessions began: before there were policemen and private, peering eyes, there was the all-seeing eye of God, and there were priests. But these days, the setting of such dramas is no longer the church or the confessional booth: it’s an interrogation room, where good & bad cops abound alternately; sometimes, it’s a courtroom, where lawyers inquire. Very human (& wigged!) judges or juries stand in for an all-knowing God. Not pretending, this time, to be all-knowing (maybe that’s where religion made a colossal mistake; people value their privacy, and God can be a nuisance sometimes) – but no less powerful or authoritative for all that.

Courtroom dramas in film have more often than not concerned themselves largely with the ‘crime’, the question of guilt – they’re little more than ‘whodunnits’, in this respect. Only with a few more lawyers than you’d otherwise have (and fewer Raymond Chandler-esque sleuths). Witness for the Prosecution (1957) springs to mind – Billy Wilder’s scriptwriting/directorial brilliance meets Agatha Christie’s genius for intrigue, suspense, and table-turning dénouements; add brilliant performances from Marlene Dietrich and Charles Laughton to the mix, and you have a rip-roaring winner of a film. But great as it is, the film does only this – concern itself with questions of guilty or not guilty, and if the latter, well then, who dunnit???

In the same year as Witness for the Prosecution, 1957, another ‘courtroom drama’ came out. It wasn’t a blockbuster hit like the former – despite a great critical reception (it was nominated for three Academy Awards, while Witness got six nominations), it fell flat financially. People put this down to any number of things – the fact that it was a low-budget production with only one ‘big’ Hollywood name to glamorize it (Henry Fonda); the fact that it was stark and minimalist, using largely only one set throughout and shot in black & white, at a time when technicolour was exploding and enthralling. It was only many years later that this film garnered the recognition it so rightly deserves (but it garnered well – it’s now considered one of the finest films ever made, ranking 6th on IMDB’s Top 250 and highly on numerous other AFI/critical lists).

To call ‘12 Angry Men‘ a ‘courtroom drama’ is technically inaccurate – surprisingly (to me, anyways), most of the film takes place not in the courtroom itself, but in the jurors’ private room. (Only about 2-3 minutes of the total film take place outside of this room, and only about 1 minute or so at the beginning is in the courtroom itself… its subversion of generic expectations begins with the set!). In this room, 12 men – some of them very angry ones indeed, as the title suggests! – have to decide upon a verdict for a trial they have just witnessed in the criminal court. Guilty, or not guilty? But the film is not so much an odyssey through suspense & titillation for the audience as it is a meditation: an examination of prejudice, personality, vendetta, doubt when they are all elements in the juridical process, aspects that contribute towards that fateful decision. (In this case, the defendant will get the death penalty if he is found guilty.)

There are safeguards built into the juridical process, of course, to prevent against the personal and the facile: “This is the remarkable thing about democracy,” says Juror #11 at one point. “That we are…notified by mail to come down to this place and decide on the guilt or innocence of a man we have not known before. We have nothing to gain or lose by it.” The jury is made up of 12 anonymous strangers; we never learn their names (until the very end, where we learn two), they do not know each other, and they do not know the defendant. This is the ideal of impartiality. Not only this, but their decision as a jury has to be unanimous – 12 votes, no less, either way. Otherwise it will be a ‘hung jury’, and the trial will have to take place again.

The case seems pretty straightforward – to borrow a cliché and quote Juror #3 (I think?), an ‘open & shut’ one. The jurors smoke, chatter, joke, but are ready to go straight to the business of voting within a few minutes of entering the room. 11 vote guilty; 1 man, irritatingly, prolongs the debate by voting ‘not guilty’. Henry Fonda’s beautiful, benign, beloved face positively radiates with goodness (for of course it is Fonda, Juror #8, who votes ‘not guilty’ – “It’s not easy for me to raise my hand and send a boy off to die without talking about it first”). The audience can pretty much see where this will go: one of two ways. Either Fonda, the lone hold-out, convinces the other eleven that he is right, or they convince him. And either way, the plot has to be damn good (the first route is hard, and the second too easy), and Juror #8 an orator of magnificent proportions. But our expectations are quickly disappointed: Juror #8 has no definite idea about the boy’s innocence. “I don’t know,” he says, or, “I’m not sure.” No Marc Antony he, here to turn the auditors’ ears to his point of view in one fell swoop.

Henry Fonda winning hearts (& verdicts).

To cut 96 minutes of running time very, very short indeed: ultimately, Juror #8 does manage to convince his audience one and all to change their votes to ‘not guilty’. What makes this film so fascinating is that he does it not by proving the defendant’s innocence, but by invoking the premise of ‘reasonable doubt’. The audience leaves the movie not knowing, ultimately, whether the defendant is worthy of this verdict – but the film tells us not to care too much about that. Where there is doubt, there cannot be death. Err always on the side of innocence (& life), if you must. Perhaps this doesn’t sound like such a big deal; after all, the film fundamentally only expounds that very old tenet, harking back to the Romans (“Ei incumbit probitio qui dicit, non qui negat” – “The burden of proof lies with [he] who declares, not [he] who denies”). Expressed more pithily these days as ‘innocent until proven guilty’.

It sure sounds easy enough – after all, we all know it, don’t we? But the film delineates beautifully how distorted even such a constitutional tenet can become in practice, even unintentionally. How oh-so-much harder it is to stick to in our quest for justice or legal integrity, easy though it is to espouse, learn, recite. We perhaps don’t even realise that we violate it. The twelve jurors are simply human – they’re the same mixture of good and bad and kind and patient and impatient, prejudiced, bitter, shy, overly-rational, overly-emotional that you’d get with any random selection of twelve people in a room. (Here’s a fun fact for everybody: Juror #2, the shyest and meekest of them all, is actually played by the actor who voices Piglet in Winnie the Pooh! I knew I loved him from the get-go, and now I know why!)

The three jurors who complicate Juror #8’s particular quest for justice, however, are jurors #3 (the angriest man of them all, & the last one to change his vote); #4 (a calm, highly rational, analytical man – if this film can be understood as depicting types, then he’s your scientific-objective man par none); and #10 (“a pushy & loud-mouthed bigot”, Wikipedia summarizes quickly and perfectly; he is the bigot in the room). Juror #4’s scientific objective stance is undermined when he is reminded of the fact that even men of science, who want to look only at the facts as clearly as possible, might miss some of the facts and so draw false conclusions. Juror #10 is perhaps the most horrifying of all – he’s a bigot. He prefaces most of his observations about the defendant with the generalizing phrase “these people” (followed usually by an unflattering characteristic of aforementioned people). One of the movies most beautiful scenes comes in the middle of a long, bigoted rant from Juror #10 – as #10 delivers his monologue of hate and stereotypes, slowly, one by one, the other jurors rise from the table in silent protest and mutiny, and stand mostly with their faces to the wall. It’s a real splendid tableau from Sidney Lumet – astonishing, powerful, and emphatic in what the film rejects. It’s probably one of the movie’s most memorable visual moments. (To watch the scene, clicky here! It’s almost difficult to believe that this is Sidney Lumet’s first feature film, because it is so very brilliant even from a technical/directorial point of view.) Says Juror #10, in perfect earnestness:

Look, you know how these people lie, it’s born in them! I mean, what the heck? I don’t have to tell you – they don’t know what the truth is. And lemme tell ya, they don’t need any real big reason to kill somebody either.

So many things about this moment: a blatant, explicit example of prejudice – the film in no way wants to make this subtle, and why should it? It’s familiar enough rhetoric to everybody. The ‘these’ and ‘them’ at whom the prejudice is directed is also by & large open-ended, which makes it a critique of all prejudice and classifications. The audience knows very little about the defendant: he’s 18 years old, on trial for parricide, and he’s from the slums. He’s uneducated, or foreign (“don’t even speak good English” says one juror; the irony isn’t, of course, lost on his immigrant neighbour). Roger Ebert, in his review of the film, suggests that the defendant “looks ‘ethnic'” – “he could be Italian, Turkish, Indian, Jewish, Arabic, Mexican”. Juror #10’s prejudice could be based on anything: a class prejudice, perhaps, or a race prejudice, or against immigrants. Anything, but it doesn’t matter: it is Prejudice with a capital P. The universal archetype of all prejudice, everywhere. And the movie is about justice for every man (everyman), an ideal that is not to be distorted or thwarted by any myopic understanding of social groups.

Brilliant tableau. Juror #10 is baffled by what’s going on around him.

Juror #3 is the hardest juror to win over – he is the last to change his vote, and the moment is a climactic one. His problem isn’t even as easy to dismiss as prejudice can be (Juror #10 is told in no uncertain to shut up and not speak again); his ‘guilty’ vote stems from the personal. The defendant is on trial for parricide, and Juror #3 has been struck by, and is now estranged from, his own beloved son. It seems he wants to condemn all sons for his own problems; at the very least, he definitely wants this one, another ungrateful one like his. Perhaps he is yet another embodiment of that horror of parricide that stories have been fascinated with from the ancient Greeks till now – a vague but emphatic and persistent horror. The history of literature, for one, is strewn with the bodies of dead fathers; from Oedipus to Karamazov, the same horror emerges. Parricide everyone agrees is fundamentally murder, another homicide, and yet why does it always feel like something peculiarly more, something fundamentally more unnatural? Remember the Defense Attorney’s speech, which comes at the famous Karamazov trial; the whole trial section of the book (The Brothers Karamazov) is amongst the best things ever written, one of the most beautiful, poignant, and elucidating sections in all of literature. All that, and brilliantly tense and dramatic too. The Defense Attorney on parricide and fathers is worth quoting at length:

“It is not only the totality of the facts that ruins my client, gentlemen of the jury,” he exclaimed, “no, my client is ruined, in reality, by just one fact: the corpse of his old father! Were it simply a homicide, you, too, would reject the accusation, in view of the insignificant, the unsubstantiated, the fantastic nature of the facts when they are each examined separately and not in their totality; at least you would hesitate to ruin a man’s destiny merely because of your prejudice against him, which, alas, he has so richly deserved! But here we have not simply a homicide, but a parricide!…

…Yes, it is a horrible thing to shed a father’s blood – his blood who begot me, his blood who loved me, his life’s blood who did not spare himself for me, who from childhood ached with my aches, who all his life suffered for my happiness and lived only in my joys, my successes! Oh, to kill such a father – who could even dream of it. Gentlemen of the jury, what is a father, a real father, what does this great word mean, what terribly great idea is contained in this appellation?” – The Brothers Karamazov, Fyodor Dostoevsky

The key of course is in “such a father” – for this is the Defense Attorney speaking. He goes on to make his defense around the fact that Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov (the murder victim) was not “such a father” as he had described. “[S]ome fathers are like a calamity,” he points out; Karamazov (Sr.) was one such. This speech is precisely what Fonda needs, in 12 Angry Men, to deliver to Juror #3; the drama of the thing lies in the fact that the boy’s defense lawyers are, unfortunately, not very good – he lucked out in a way even Dmitri Karamazov didn’t. This important speech goes unsaid, though its sentiments perhaps not unlearned. (I really do wonder how indebted to Dostoevsky Reginald Rose was….!). As Juror #3 finally breaks down at the end and chokes out his verdict of ‘not guilty’, perhaps he too acknowledges that some fathers can be calamities. This time, wondering about himself.

This post began with Dostoevsky, and it seems like a good idea to end with Dostoevsky too. In narratives of suspense, thrill, investigation, the pressure point always falls on the ‘crime’ of ‘crime & punishment’: perhaps as consumers of movies and books and TV shows, it’s because we have an insatiable curiousity, an unquenchable urge to know (whodunnit?). So very often movies and books end with the revelation (think Agatha Christie, of whom I am a great devotee!); the gory rest is silence. We know punishment will follow once the criminal has been caught or ascertained; every one of us does, but we don’t care to see the punishment or think about it. What is extraordinary about 12 Angry Men is that it forces us to think about the punishment first, and about the crime later (if at all). To quote brilliant, wonderful Ebert again, “[the film] is not about solving a crime. It is about sending a man to his death.” It’s not a plea to end all punishment, of course, but it is a valuable reminder that nowadays crimes & punishments are meted out in the human, not heavenly, sphere. Judges, juries, even witnesses are not all-seeing, all-knowing beings; worse, they have their own problems and prejudices to deal with. They are fallible and myopic, because people are. “You’re talking about a matter of seconds! Nobody can be that accurate!” cries out Juror #3 at one point in exasperation. “But testimony that can put a boy into the electric-chair should be that accurate,” replies Juror #8. Whether you read into this movie a critique of the death-penalty (because after all, surely all human testimony can be subject to reasonable doubt?) or whether you merely read into it a demand for greater care and consideration in deciding upon verdicts… it’s a lesson worth remembering. And this film is worth watching. And boy oh boy, it’s slightly corny to say it, but personally, I think it’s life-changing.

Some interesting links for folks:

The entirety of this film is available to watch, for free, on Youtube.

Roger Ebert’s review of the film is excellent (because he was wonderful and amazing!), and also has some interesting points in it about Lumet’s camera techniques.

An essay on the movie by Thane Rosenbaum, for the Criterion Collection.

And finally, the screenplay for the movie from Screenplay Explorer. (Note: it was a TV drama first, & I’m not entirely sure whether this is the script for the TV version or the movie version.)